Beyond Meat’s pullback in China highlights weak demand for plant-based meat, driven mainly by taste and price gaps. Meanwhile, China is pushing three “new protein” routes: texture-focused “su rou (plant-based)” at lower cost, scaled pilot cultivated pork (2,000 L), and broader bio-manufactured proteins via synthetic biology and precision fermentation.

News that Beyond Meat has closed its flagship store on Tmall has stirred fresh debate in China’s alternative-protein space. The timing is striking: at the same time, the Tengchong Scientists Forum– often dubbed a “tech Davos” – featured upbeat talk about how fast replacement proteins could evolve.

Taken together, it is a cold shower and a hot spotlight. So where does the market go from here?

From “first stock” status to a China pullback

Founded in 2009, Beyond Meat was among the earliest US plant-based meat companies to gain scale. Part of its early fame came from high-profile backers, including Microsoft founder Bill Gates and actor Leonardo DiCaprio.

In May 2019, Beyond Meat listed on the New York Stock Exchange, becoming the world’s first publicly traded “fake meat” company. On its first day, the share price jumped 163% to USD 65.75, and it continued rising for months, peaking at nearly USD 234 per share.

Soon after listing, Beyond Meat entered China through a partnership with Starbucks China. In April 2020, it set up a wholly owned unit, Beyond (Jiaxing) Food Co., Ltd., with registered capital of USD 22 million. About a year later, Beyond Meat unveiled a “world-class” plant-based meat factory in Jiaxing and, beyond beef and poultry products, launched its first China-tailored innovation: Beyond Pork.

From there, Beyond Meat expanded partnerships in China with brands and retailers including KFC, Pizza Hut, Jindingxuan, Hema, and Metro. It also built out e-commerce across Tmall, JD.com, and Pinduoduo. Product applications moved beyond burgers into familiar Chinese dishes such as mapo tofu, zhajiang noodles, dumplings, and xiaolongbao.

Beyond Meat has positioned its products as made entirely from plant ingredients, designed to mimic the flavour, texture, and mouthfeel of animal meat. It says peas and rice provide “high-quality protein,” while potato starch and coconut oil help deliver juiciness and texture. Beet juice is used to create a “meat-juice” effect.

A chill sets in

Around 2020, African swine fever (ASF) disruptions left China facing pork supply tightness. A wave of companies – domestic and international – moved into the plant-based “meat” category around the same time. That included Cargill’s PlantEver, Nestlé’s Harvest Gourmet, Unilever’s The Vegetarian Butcher, and A-share listed firms such as Shuangta Food and Jinhua Ham.

Another global player, Impossible Foods, told AgriPost at the start of 2020 that while it had no concrete plan then to launch in mainland China, it wanted to move quickly. “If there is no sound, safe, assured, and sustainable Chinese food system, there cannot be a sustainable global food system,” the company said, citing China as accounting for 28% of global meat consumption and describing demand as rising sharply.

Reality has proved tougher. Impossible Foods still has not entered mainland China. Beyond Meat’s Jiaxing plant stopped production earlier this year, and Nestlé and Unilever had already paused related business even earlier. Feedback across channels points to familiar friction points: a taste gap versus real meat, and weak price competitiveness.

The downshift is not limited to China. Beyond Meat’s revenue declined year after year from 2021 to 2024, at USD 465 million, USD 419 million, USD 343 million, and USD 326 million, respectively. Net losses over the same period reached USD182 million, USD 366 million, USD 338 million, and USD 160 million.

By the close on December 18, Beyond Meat’s shares had fallen to USD 1.04, giving the company a market value of just USD 472 million.

China’s home-grown “su rou” play: fix texture first

Across global plant-based meat development, most products start with legume proteins and rely on additives to tune flavour toward animal meat. A Chinese molecular physicist entered the space seven or eight years ago with a different angle: reshaping protein structures through physics so they behave more like animal muscle in texture and bite.

Wu Qi

Wu Qi, an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and director of Shenzhen University’s Food Science and Processing Research Center, argues that “素肉” (su rou/ plant based meat) is a better fit than imported labels such as “plant-based meat” or “fake meat.” In his view, East and West are solving different problems. Western cooking, he said, often prioritises flavour because preparation is simpler. Chinese cooking is more complex, and “the first thing is to solve mouthfeel.”

That mouthfeel, Wu said, comes down to how macromolecular chains align, entangle, and knot – something physics can address.

Wu’s team went beyond common modern Chinese “vegetarian meat” approaches like extrusion structuring, which push soy globulin into aligned, fibrous textures. They stretched soy protein further and then connected it through entangling, aiming for water content above 60% – closer to the composition of animal meat.

At the 2025 Tengchong forum’s “Biodiversity and Modern Agriculture” session, Wu said production costs for this su rou could be kept at no more than CNY 20.00 per kg (USD 2.79 per kg). Yet the consumer price looks very different: a 500 g bag of su rou (plant-based) “pork belly” chunks on a major e-commerce platform is priced at CNY 35.00, which is equivalent to CNY 70.00 per kg (USD 9.75 per kg). The store’s sales over the past month were 14 units.

Wu also shared feedback from Yihai Kerry’s Shanghai team after tasting his su rou samples. The group reportedly agreed that both appearance and mouthfeel resembled beef. Visually, fat and red meat looked naturally integrated; stir-fried dishes appeared glossy and convincingly red. In texture, the product had chew, and when pulled apart by hand it showed clear, meat-like fibres. The main shortcoming, Wu said, may be that the application method affected flavour, leaving it short of “beef fat” aroma.

Wu remains optimistic. China’s national meat consumption market is about CNY 2.5 trillion (USD 348.19 billion), he said, and replacing 10% would be CNY 250.00 billion (USD 34.82 billion).

Cultivated pork scales up to 2,000 L

Plant protein is only part of the story. Cultivated meat is starting to show larger-scale engineering progress in China as well.

Zhou Guanghong, former president of Nanjing Agricultural University, and his team, who developed China’s first piece of cultivated meat back in 2019, announced another milestone: they have built what they describe as China’s largest pilot-scale cultivated meat facility. The project has completed what it calls the world’s first scaled pilot production of cultivated pork using a 2,000 L bioreactor.

The operator, Nanjing Zhouzi Future Food Technology Co., Ltd., said the development marks a key leap from lab R&D to engineered system production, laying a foundation for commercialisation and global competition in food tech. It also said China’s cultivated meat technology is now in the international front ranks, and that cultivated pork is internationally leading.

The new pilot plant is described as having capacity of 10–50 tonnes of cultivated meat products per year. It is intended to support optimisation of key engineering parameters, production cost modelling, and the design of future 10,000-tonne-scale production lines with reliable data and an engineering template.

The company also outlined a parallel R&D approach: “general-purpose products” alongside “featured innovation.” Using cultivated pork as an ingredient, it said it can mimic pork belly form and mouthfeel via 3D printing. It also described a “honeycomb meat” combining mushroom protein with cultivated pork to create a porous structure and a layered, springy tenderness. Another concept, “clear soup jelly with crispy meat chips,” uses a broth co-cooked with cultivated meat to form a light jelly, paired with baked crispy cultivated pork slices, reinterpreting traditional savoury notes through molecular gastronomy techniques.

These results, the company said, show how shape, flavour, and texture can be highly configurable, opening routes from mass catering to high-end cuisine, and from everyday consumption to experiential formats. It added that, so far, cultivated meat products from 10 companies across five countries (Singapore, the United States, Israel, Australia, and the United Kingdom) have been approved for market entry. In 2025 alone, it said, six new cultivated meat products received regulatory clearance, signalling faster market expansion.

“New-type protein” goes wider than meat analogues

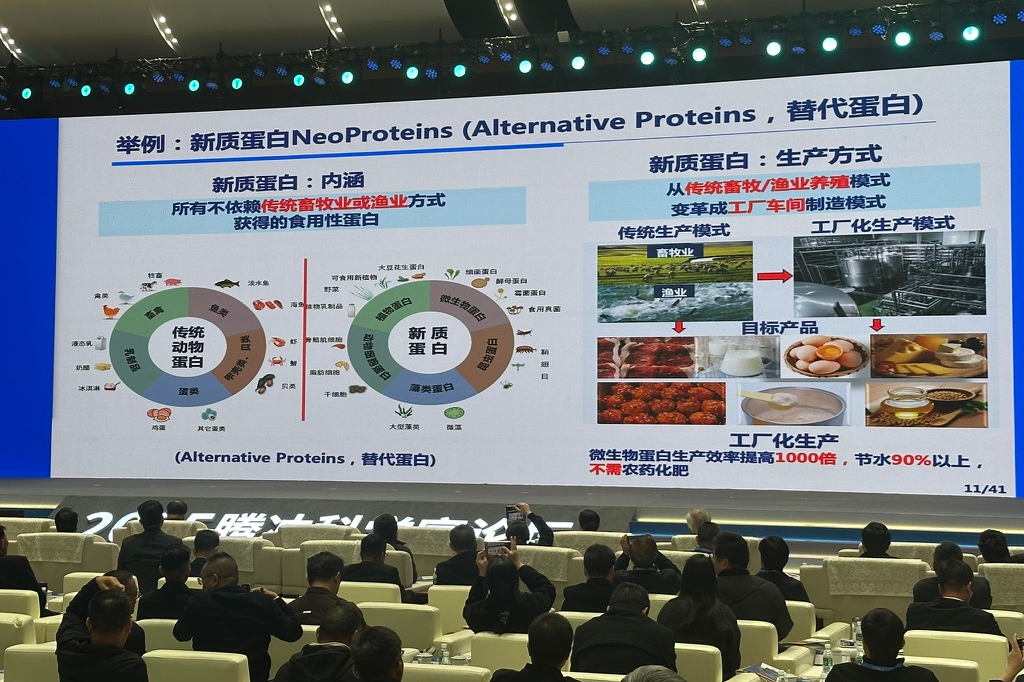

At the Tengchong forum, Chen Jian, an academician of the Chinese Academy of Engineering and former president of Jiangnan University, pushed the conversation broader still. Beyond plant-based and cultivated meat as “alternative proteins,” he proposed a wider umbrella: new-type protein. In his framing, that includes microbial protein, insect protein, and algal protein.

Chen Jian

Microbial protein, he said, can be split into microbial biomass protein used as a primary food ingredient and microbial functional proteins used as food components. China started later, but Chen said the past three years have seen rapid growth, with many already reaching industrial application. He cited Shougang Lanze, which uses industrial tail gas to produce ethanol-clostridium protein, and Angel Yeast, which has built multiple brewer’s yeast protein production lines globally.

Chen described the space as a “hundreds-of-billions” yuan track, with the core challenge being how to produce at scale and at low cost. He said that requires two moves: first, building the “cell factory” through synthetic biology, using cheaper substrates while delivering industrial traits such as fast growth and high protein content; and second, running the cell factory through precision fermentation, including co-producing multiple products to reduce costs.

In Chen’s view, this belongs to “bio-manufacturing,” and future meat, egg, and dairy foods could all be supplied through such methods. He described synthesising egg proteins like ovalbumin, ovotransferrin, and ovomucin through synthetic biology, then blending them into egg-like products. Similarly, he said, synthetic biology could manufacture milk nutrients such as lactoferrin, casein, globulin, and albumin, then blend them into products similar to natural milk or designed for specific functions.

Under Chen’s definition, any edible protein not obtained through traditional livestock or fisheries systems can be called “new-type protein.” The shift, he said, is from farm-based production to factory-style manufacturing – with implications for protein supply security, higher-efficiency protein output, improved nutrition and health, and global sustainability.

A Nature article was cited as noting that if fungal protein replaced 20% of global beef consumption by 2050, annual deforestation and related carbon emissions could be reduced by 56%. Boston Consulting Group has also projected that by 2035, the global new-type protein market could reach USD290 billion, including 69 million tonnes of plant protein, 22 million tonnes of microbial protein, and 6 million tonnes of cultivated protein – about 11% of total protein supply.

AgriPost.CN – Your Second Brain in China’s Agri-food Industry, Empowering Global Collaborations in the Animal Protein Sector.